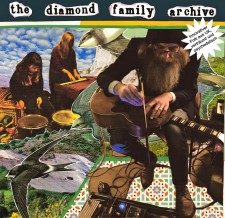

ENTFÄLLT! +++ The Diamond Family Archiv (UK)

Leider fällt das Konzert aus, Laurence kommt aber bestimmt wieder!

Leider fällt das Konzert aus, Laurence kommt aber bestimmt wieder!

Laurence Collyer ist wieder bei uns und hat diesmal 2 Musikerinnen an Bord: „The Diamond Family Archive“ liefern magnetisierende Live Shows mit Autoharp und Akustikgitarre, vielen Effektpedalen, dröhnenden Keyboards, Percussion,Gesang, Tape Delays, Loops und Rückkopplungen, Geigenbögen, Kinderspielzeug und kaputten Becken. All diese Elemente kommen zusammen, um eine Musik zu erschaffen,die Echos von Post-Rock, traditionellem American Folk, spiritueller Soul Musik, Psychedelic Rock und Lo-Fi enthält.

Fuß-stampfende, Finger-pickende, brüllendes Feedback vs. dem Geräusch einer fallenden Stecknadel – zerbrechliche, träge Anmut. Geister-Rock.

-------

In a rural kitchen, he’s sitting amidst a wildly disorganised collection of cables, playing a stripped unvarnished arch-top guitar with the words ‘Dorset, Creekmoor’ stencilled on the scratch-plate. Opposite him sits a pump organ, stripped to a skeletal frame, the reeds and mechanics clearly visible, the wires from stealthily placed contact pickups meet with a digital effects unit and a dusty old amplifier. At his feet is a pedal board the size of a child’s bed. He continues to play as we speak, conversation punctuated by the hollow whistle of his half briar. This is Laurence Collyer. Or as he is better known, the Diamond Family Archive. Laurence is referred to, almost exclusively as a folk musician, admittedly, descriptions of his work seem forced to rely on other adjectives or prefixes which serve, in a way, to disclaim the work’s separation from the ‘tradition’ or rather the repertory system that defines much of what we consider to be folksong. This is important when considering Collyer’s output.

It is not that Collyer is against his work being described as folk, but rather he is reluctant to declare himself as such. His idea of what a folk musician is comes from a binary of scholarship and generational learning, both of which he lacks. He feels that his inability to join in with a traditional ‘session’ excludes him somehow from the tradition itself. This typifies the discursive lack within folk music. What are these new songwriters excluded at once from the scholarly, taught tradition but excluded too from the immediate label of ‘pop’ by their use of traditional technique and instrumentation? It seems conversationally and journalistically appropriate to use folk as a pronoun, but as soon as we consider attempts at solid definition or classification they become dislocated. Perhaps this is absolutely fitting. Contemporary folk singers should not fit easily within the tradition, for one very simple reason; the nature of ‘the folk’, that is people, us, has changed. If we consider that there was (and I write this fully understanding that the ‘fact’ of this is at least various and muddy) a ‘peasant’ class of secular song, it has at all stages reflected its own time and culture. Even when ancient songs are reborn, it is with different motives and contexts. Be it one of metaphor, allegory, nostalgia or simply preservation, the reason of/for folksong shifts along with the times of its performance. It is natural for the work of an artist like Collyer to run alongside or draw musically and technically from tradition whilst jarring somewhat with its ‘rules’ or norms. This is arguably, quite simply, how the chronology of music travels. The nature of folk music changes with its subjects. There is no music in this cartography that develops in isolation from others. We no longer live a life of community subsistence without the seductive charms of the media, so writing about one’s life and culture in a contemporary fashion naturally reflects this fact. Besides, is it not strange, or perhaps ironic, that the secular music of a people, passed on through aural transmission should be in some way precious about the means or uses of/in its performance?

But it is not merely in its techniques and instrumentation that the Diamond Family Archive finds itself within the embrace of what we call folksong. The narrative themes consider those things that are common and often inevitable within the history of song. Things we associate so strongly with the folk music of the British Isles, and any site of migration or diasporic growth in the English-speaking world. Indeed, this probably applies to all folk traditions, but here, let’s stick as closely as we can to the cultures that inform this particular work. Collyer’s music is one of inhabited landscape. The events concern love, death, work, faith and drink like many songs, ‘folk’ or otherwise, but there is a thread running through the stories which binds them and gives them the sense of cohesive, emotional potency that I have always found within Laurence’s work. This thread I feel I can best describe as being a fascination with the relationship between home and regret. It should be noted that ‘home’ for the Diamond Family Archive is always somewhere else, somewhere that the narrator is not. It can be visited or remembered, but seemingly never lived in, except within the past. These songs are full of desire, but they are almost bereft of hope. If there is hope, then it is only for a temporary break from the consuming pessimism of the truth.

And as we talk, of his upbringing, his personal cartography, his itinerancy, in short his life, it is easy to see why. Not that Collyer is especially downtrodden or sad, but that he joins the countless among us who are fundamentally displaced. His gift is that he can articulate this experience. He does not complain and he is rarely explicit. He simply allows his experience to weave itself through his songs. This is by no means just lyrical however; the music itself is built from his lifestyle. The Diamond Family Archive is a vessel for the constantly shifting atmospheres of his travels. He seems unable to do anything with music but evoke the landscapes, waters, wildlife and loves that he encounters, without, it seems, ever attempting to describe them, either musically or in language. The descriptions are simply of his failure to hang on to them. It is then, a sound that smacks of sincerity.

It is an uncomfortable feeling to write about a friend and collaborator, particularly in reference to recordings that one has played on. But our collaborative relationship and our conversations on these subjects perhaps make me a well-qualified voice. I hope so. I can leave our conversations in that kitchen, knowing that they can be picked up in any other place, but he will still be playing as we speak, and what he plays will be as sad as anything I have heard.

(Johny Lamb / woodlandrecords)

__________________________

https://www.facebook.com/laurence.collyer/

http://thediamondfamilyarchive.blogspot.de/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2q7I8h0dX1c